The “who” of young adult (YA) mysteries applies in two ways: who are the characters, and who are the readers? A third dimension is the interactions among all of these.

The “who” of young adult (YA) mysteries applies in two ways: who are the characters, and who are the readers? A third dimension is the interactions among all of these.

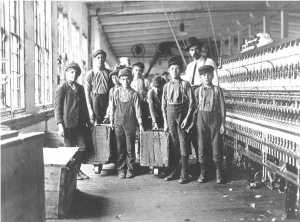

The photos shown here are of children in the workforce. In America, the ban on child labor is only a couple of generations long —  but what a difference it has made it what’s expected of kids, from behavior to learning to standard of living! It’s worth considering that enormous gap, when writing for young adults, as I can’t say this often enough: Today’s teens are NOT “like we used to be.” To prove this to yourself, write a list of your three favorite things to do when you were 12 or 13; now, look at how the teens around you are “doing” each of those actions.

but what a difference it has made it what’s expected of kids, from behavior to learning to standard of living! It’s worth considering that enormous gap, when writing for young adults, as I can’t say this often enough: Today’s teens are NOT “like we used to be.” To prove this to yourself, write a list of your three favorite things to do when you were 12 or 13; now, look at how the teens around you are “doing” each of those actions.

It’s possible to dodge this difference in activity by placing YA mysteries in a past time slot, and I’ve appreciated the gift provided in that form. But even then, the author is in a sense a time-translator. As a very basic example, when I began telling stories regularly, I often told “Rumplestiltskin” in local schools. But I began to realize that few students could picture “spinning straw.” Eventually I changed the tale to reflect the audience.

In the “Hunger Games” series, Suzanne Collins leapfrogged this time gap in two ways: by creating an impoverished post-apocalyptic world in which Katniss, our main protagonist and problem solver, lives, where bows and arrows (easily described!) are standard, and by placing her powerful figures in a sci-fi world that’s so far advanced compared to what Katniss knows, that she mostly marvels at it, and grasps uses but not mechanisms. Her connections with other teens, though, are where the story’s power lies. And those — thank goodness! — are not envisioned as changing a lot.

Yet here too, research on the “who” can be vital to how a YA novel — particularly a mystery — is framed. What We Saw at Night, the compelling start of a YA mystery series by Jacquelyn Mitchard, presents teen sexuality in new ways that won’t mesh with “how most of us did it (or felt about it) when we were teens.” A mystery set “now” may need to face today’s conflicts around sexuality and forms of affection, as well as forms of power and coercion.

The Internet can be an enormous resource for YA authors who aren’t living with teens. Articulate, funny, angry, discreet or graphic, the teens blogging today provide a doorway into the Brave New World of their experience and ideas. I’ve sought out opinions, music titles, book favorites, clothing changes, even tattoo trends, in this way. Have an adventure — try it for yourself!

One last quick mention of the other “who” of YA mysteries: readers. Working at our local county fair last month, I met a lot of young teens who already knew one or more of my YA mysteries and who wanted another. But this is really the exception for me — when I’m in bookstores, the “readers” (disguised as “I’m buying this for my grandchild”) are far more likely to be adults. And in both schools and libraries, adult readers are the gatekeepers for teen fiction.

Who are you writing for? Who are you writing about?

Next week: “What.”

Pingback: Pen, Ink, and Crimes